Sometimes the joy of research for my book has overtaken the writing process. I can't stop reading about Chaplin, Kelly and Jobs. There are over 600 book on Chaplin with most being regurgitations of previous works. I'd estimate that there are only two dozen really good works. There are 85 movies to watch also and each must be watched two or three times to really see the many nuances in his work.

Gene Kelly has far fewer books about his life and there are only 6 or so that are noteworthy. He has 45 movies and, again, each must be watched numerous times. I say, must be watched, but for Kelly and Chaplin, it's a joy and I'm amazed with each viewing as I see different aspects of their genius.

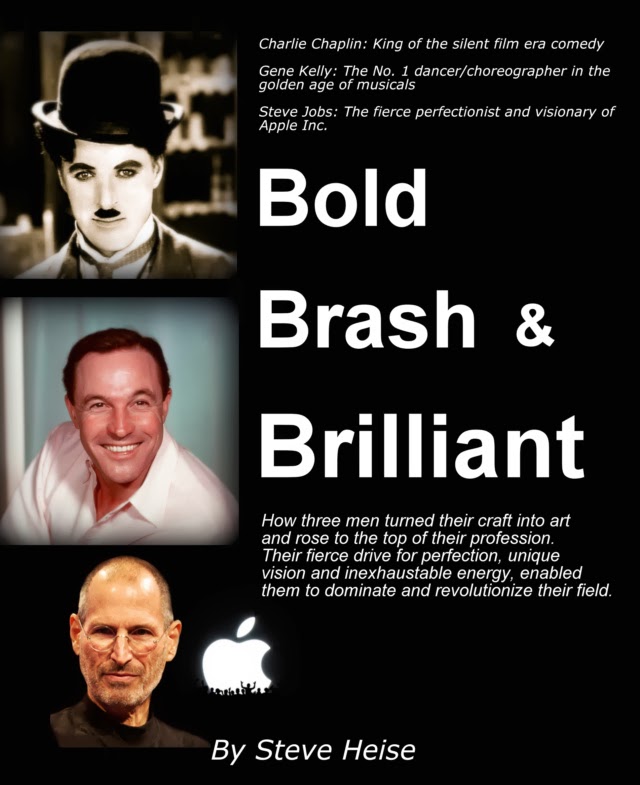

Steve Jobs is almost the outlier in this group, because he was not an entertainer, but with the premise of the book being perfectionism, he fits. All three men were brutal to work for, demanding, mean in some cases and egotistical, but all were only interested in providing the best product and getting the best from their people.

Chaplin and Kelly forced actors to work through dozens of takes on a single scene until it was right. Chaplin often went into hundreds of takes for one scene. Steve Jobs would force workers to go back to the drawing board over and over again to got to the perfection he envisioned for a product of feature. He would study hundreds of prototypes until he was satisfied.

Two or three books come out each year on Chaplin. Only a book every two or three year or so on Kelly is published. Steve Jobs is the subject of many books from basic biographical accounts to studies of his management and presentations styles.

I could be totally happy just doing research, but the book calls and I need to finish.

In March 1936, during a tour of Japan, Charlie Chaplin called in on the Kabuki-za theatre in downtown Tokyo. A photograph commemorates the visit: Chaplin, handsome, silver-haired and moustache-less, stands beside the kabuki master Koshiro Matsumoto VII, grinning broadly and pointing at the actor’s elaborate costume, obviously impressed.

Seventy-eight years and seven months later, during the Tokyo International Film Festival, Chaplin returned to the Kabuki-za in one of the best ideas a film festival has ever had: a double-bill of his silent 1931 masterpiece City Lights and a short kabuki play called Shakkyo – The Stone Bridge – about a fantastical lion chasing two pesky humans off his turf.

Kabuki is a highly stylised form of classical Japanese theatre, all ghosts and samurai, swathed in mist and myth – hardly an obvious match for the misadventures of a tragicomic tramp in earthy, clattering interwar America. But seen side by side, they’re such obvious cousins you half-expect the Little Tramp to wander on stage, edge gingerly past the lion and, in turning to flee, fall over the side of the bridge.

Both art-forms were born within spitting distance of the gutter: silent comedy in the music halls where performers like Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy honed their craft, and kabuki in the pleasure quarters of old Tokyo and Kyoto, where acting troupes performed light-hearted, often bawdy plays about the struggles of everyday life.

Each one relies for its impact on its performers’ faces, which were stylised almost to the point of abstraction with thick, white make-up. Each gleans extra dramatic power from a musical score: in kabuki’s case, it’s performed by a 16-piece orchestra of wooden flutes, drums, voices and shamisen (imagine a triangular banjo played with a fish-slice).

The action in both is fast and energetic, but choreographed as meticulously as dance, with ingrained routines that even experts took years to master. Both attracted trouble in their heydays, and the performers’ private lives became fodder for public scandal – stories about storytellers.

But perhaps most crucially, both are able to speak volumes about the experience of being human without recourse to human speech – something that makes both art-forms timeless and borderless, for all their cultural idiosyncrasies. Silent comedies have been enjoyed since the earlier days of cinema, while kabuki has been performed since the 17th century. And that night, its spiritual home shook with laughter at the universal genius of Chaplin.

City Lights may be Chaplin’s greatest film. He started work on it in 1928, when every studio in Hollywood and cinema in Europe and America was gearing up for the age of sound, but it’s defiantly, triumphantly silent. Chaplin’s Little Tramp meets a poor, blind young woman (Virginia Cherrill) selling flowers on the roadside, and, in the kind of misunderstanding that only silent comedy can pull off, she mistakes him for a millionaire. Delighted by her error, he plays along – and then, later that same day, he befriends a real millionaire (Harry Myers), who stumbles down to the river in a drunken stupor, with the intention of drowning himself.

These people are the Tramp’s two closest friends, but the friendships are only possible because neither actually sees him for who he is. Whenever he sobers up, the millionaire has him thrown out of his house, while the flower girl feels the cuff of his suit and thinks of a gentleman rather than a drifter. Desperate to live up to this imagined version of himself, the Tramp takes two jobs to help pay the flower girl’s rent: firstly as a street-sweeper, and then as a reluctant boxer in a prize fight.

The 12-minute sequence in which he psyches himself up for the match and then skips frantically around the ring, determined to keep the referee between himself and his huge opponent at all times, is the best and funniest thing Chaplin ever did. The scene is so precise, it isn’t acted so much as danced. It’s as abstracted, and perfected, as kabuki.

In 1931, a kabuki troupe visiting the United States went to see Chaplin’s City Lights in the cinema, and returned home with astonished stories of this man who combined comedy and pathos as brilliantly as the best in their discipline. They went on to adapt their memories of the film into a kabuki play called Yasu the Bat. In place of the boxing scene, there’s a sumo bout.

Somegoro Ichikawa, the great-grandson of Koshiro Matsumoto VII, played the lead role of the lion in Shakkyo that evening, and the ghost of Chaplin was never far from the stage. The humans tumbled head-over-heels as the lion attacked like the Tramp lunging from one side of the boxing ring to the other.

The only immediately obvious difference was the colour: the stage of the Kabuki-za was almost supernaturally bright, with dazzling blue fabric waterfalls rushing past dark rocks and lush, green undergrowth, and, during the climax of the battle, while the lion’s red mane lashed out like a tongue of flame, silver petals fluttered from the ceiling like snow.

It was art and spectacle from another time, and the thousand-strong audience, styled, coiffed and primped to the edge of modernity, leapt to their feet to applaud.